In a country where over 5 million children live below the poverty line, a small elite attends schools that resemble five-star resorts more than classrooms. These institutions—commonly referred to as Kenya’s billionaire schools—represent not just wealth, but a stark and growing divide in the nation’s education system.

The Rise of Elite Education

Over the past two decades, Kenya has witnessed a dramatic rise in private international schools that cater to the ultra-wealthy. These include Brookhouse, Peponi, Hillcrest, the International School of Kenya (ISK), and Greensteds International School, among others. Many charge upwards of KSh 2 million per year, equivalent to a middle-class family’s entire annual income.

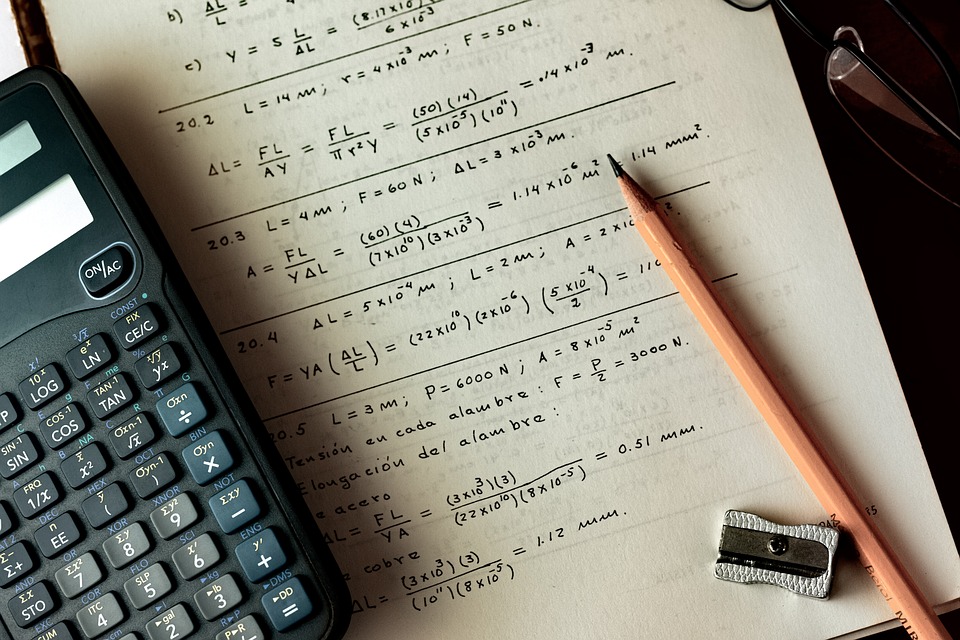

Facilities in these schools often include horse stables, Olympic-sized swimming pools, robotics labs, gourmet cafeterias, golf courses, and individual learning assistants. The curriculum is typically British (IGCSE/A-Levels) or American (SAT/IB), and students are groomed for top-tier universities like Harvard, Oxford, and Stanford.

This has earned them the nickname billionaire schools—not only for the cost, but for the kind of global wealth they attract.

Read Also: Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ: Novelist, Playwright, and Bold Voice in African Literature

Who Attends Kenya’s Billionaire Schools?

These elite institutions are primarily attended by the children of politicians, diplomats, foreign investors, corporate executives, and high-net-worth diaspora families. But there’s an emerging category: nouveau riche entrepreneurs and second-generation business moguls who see these schools as not just educational institutions but social elevators.

Attending one of Kenya’s billionaire schools is now a status symbol—an investment in a future global identity. Students wear designer uniforms, speak in accents that blur global borders, and participate in Model United Nations conferences before they’re old enough to vote.

A Country of Two Classrooms

While a few students sip frappuccinos between coding classes, millions of others attend overcrowded public schools, some under trees, with little access to textbooks or even teachers. In 2024, the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) reported a shortage of over 110,000 teachers across public primary and secondary schools.

According to a UNESCO report, 85% of Kenyan children attend public schools. These institutions are frequently underfunded, over-enrolled, and increasingly unable to compete with the globalized learning offered in the private sector.

This has created two tiers of education: one where children learn to be global citizens, and another where survival takes precedence over academic excellence. The class divide in education is no longer hidden; it is boldly institutionalized.

The Power of Prestige

The prestige of these elite schools isn’t just in their facilities or fees—it’s in their networks. Alumni lists read like Who’s Who in Kenyan politics and business. These connections, forged at a young age, often translate into internships, jobs, board seats, and access to political influence.

In essence, Kenya’s billionaire schools don’t just teach—they replicate privilege. They preserve power. And they make it increasingly difficult for social mobility to occur outside that tight circle.

This begs the question: is education still the great equalizer, or has it become one of the most entrenched tools of inequality?

Read Also: Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ: African Literary Voice, Poet, and Cornell Professor

Inequality by Design?

The growth of elite education tracks broader global trends, but Kenya’s case is unique because of the sheer disparity in national wealth distribution. According to the World Bank, Kenya’s richest 10% control over 40% of the country’s income. In such a context, access to quality education has become a private commodity rather than a public good.

Moreover, some of these billionaire schools are backed by foreign investors or multinational education firms, turning learning into a profit-driven industry. This raises ethical questions about whether these institutions are accountable to national educational goals or simply creating private utopias for the privileged.

The Psychological Divide

Beyond material differences, a psychological divide is forming. Children in public schools grow up with a limited view of what’s possible. Their exposure is local. Their confidence is often compromised by scarcity. Meanwhile, elite school students are taught to speak with authority, to lead, and to believe that the world is theirs to inherit.

When both groups eventually meet—perhaps in a university lecture hall, corporate boardroom, or ballot box—the social gap is not just economic. It’s mental, emotional, and cultural. Bridging it will take more than policy.

Can the Gap Be Closed?

Efforts to reform Kenya’s public education system are underway. The Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC) was introduced to address outdated teaching methods and promote skill development. But critics argue that its implementation has been chaotic and resource-intensive—again placing students from rural and poor backgrounds at a disadvantage.

Some propose regulation: capping school fees, taxing luxury schools more heavily, or creating quotas for disadvantaged students in elite institutions. Others suggest investing more heavily in public education, especially through infrastructure, digital learning, and teacher training.

But ultimately, closing the class divide in education will require a national reckoning. If we truly believe in equality of opportunity, then access to quality education cannot depend on wealth.

Kenya’s billionaire schools are not inherently bad. They are centers of excellence, offering world-class education that prepares students for a global future. The problem is not their existence—it’s the ecosystem of exclusion they reinforce.

When a child’s future is determined by the family they’re born into and the school they can afford, meritocracy becomes a myth. The result is not just educational inequality—it’s societal fragmentation.

For Kenya to thrive, it must address this growing educational apartheid. Because prestige should never come at the cost of a just and cohesive society.

Read Also: Education The Pillars of Personal and Professional Growth

Never Miss a Story: Join Our Newsletter