In Kenya’s rapidly evolving identity landscape, names have become more than personal labels — they are reflections of aspiration, rebellion, cultural affiliation, and sometimes, denial. As Generation Z — born roughly between 1997 and 2012 — comes of age, a silent cultural shift is underway. Many young Kenyans are abandoning traditional African names in favor of Western-sounding alternatives, raising concerns about cultural erosion, social belonging, and the future of indigenous identity.

💬 “Just Call Me Jayden”

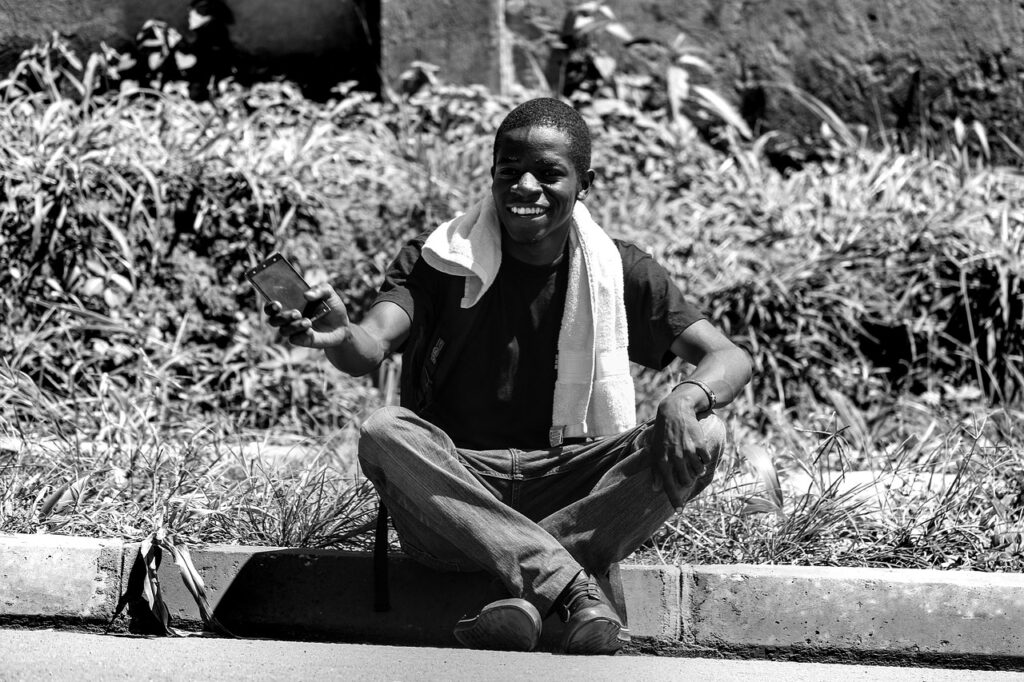

At a university in Nairobi, 22-year-old Kevin Omondi insists on being called Jayden. “It just sounds cooler. Omondi makes people ask where I’m from. Jayden is clean, neutral — and global,” he shrugs.

He is not alone. A stroll through social media handles reveals a flood of Gen Z Kenyans branding themselves as Ashley, Trevor, Zayne, or Vanessa — even when their ID cards bear names like Wanjiku, Kiprotich, or Atieno.

This naming shift is not merely stylistic. It reflects deeper tensions: between local and global identity, tradition and modernity, pride and perceived embarrassment

Disappearing Identity?

Historically, African names carried meaning — often derived from birth order, seasons, nature, clan roles, or spiritual beliefs. For instance:

- Makau (Kamba) means War-time

- Nyambura (Kikuyu) is tied to the rainy season

- Wanyonyi (Bukusu) Weeds

But today, these names are often buried under layers of colonial hangovers, social pressure, and a media environment that champions Eurocentric standards.

Dr. Grace Mugambi, a linguist at Kenyatta University, observes:

“When names lose their prestige, identity follows. The abandonment of African names by youth is a cultural alarm bell.”

The Globalization Effect

One of the major drivers of this shift is globalization. Gen Z is growing up in a world where:

- Job recruiters prefer ‘pronounceable’ names.

- YouTubers and TikTokers with foreign-sounding names dominate follower counts.

- Western pop culture paints “African” as exotic or backward.

An HR manager in Nairobi, speaking off the record, admitted:

“Some resumes with names like Achieng or Barasa are unfairly stereotyped, especially when applying to international organizations. It shouldn’t happen — but it does.”

As a result, young people preempt the bias — anglicizing their names or using abbreviations to blend in.

Shame, Class, and Name Policing

For some, African names signal rural roots, tribal identity, or poverty. In an era where polished English, curated Instagram feeds, and accent mimicry are seen as success markers, traditional names feel like a burden.

This internalized bias starts early. Many Gen Z children grow up being told to use their “Christian name” in school while their ethnic name remains buried in the birth certificate.

“My parents gave me a Kikuyu name, but teachers always pronounced it wrong or laughed. I eventually dropped it,” shares Michelle Njeri (now just “Michelle” online).

The result? A generation that views indigenous names as either irrelevant, embarrassing, or optional.

But There’s a Counter-Movement

Interestingly, even as African names fade in urban spaces, a growing Afrocentric revival is emerging among some circles of Gen Z.

In fashion, music, and literature, there’s a renewed embrace of African culture. Some youths are reclaiming their identity by reverting to their full names or proudly using traditional monikers in digital spaces.

Platforms like TikTok feature creators with names like Biko Kimani, Shantel Wairimu, and Lwanda Ochieng, showcasing African culture unapologetically.

Initiatives such as the #SayMyName campaign also challenge people to pronounce and respect ethnic names without anglicizing them.

What Names Really Carry

Names are not just convenient tags. They encode history, values, family legacies, and community belonging. Losing them means disconnecting from ancestral memory.

For example:

- Auma among the Luo signifies “one born with the back first.”

- Kipchirchir among the Kalenjin indicates one born quickly, in the early morning.

- Wafula (Bukusu/Luhya) refers to one born during the rainy season.

These are not arbitrary. They’re cultural timestamps, testimonies of who we are and where we come from.

So, Are Our Names Dying?

Not entirely — but they are under siege. The pull of global conformity is strong, but so is the pushback from cultural guardians, creatives, and educators.

To preserve African identity in a modern world, the naming system must evolve without erasure. Young people can still be global citizens — fluent in tech, art, and commerce — without shedding their roots.

Educators and parents have a critical role to play in normalizing ethnic names, teaching their meanings, and instilling pride in their origin.

What’s in a Name?

In a world obsessed with brand and image, your name is your first badge of identity. For Kenya’s Gen Z, the question is not whether foreign names are wrong — but whether African names deserve to disappear just to feel accepted.

Perhaps the more powerful stance is this:

Be Jayden — but remember you’re also Omondi.

Be Tasha — but never forget you’re Wanjiku.

Never Miss a Story: Join Our Newsletter